Playing At The Edge of What We Know

No Man’s Sky, Power, Play, and the Cycle of Expertise

I look out beyond the rings of a newly discovered planet. My sense of accomplishment fades as I realize that there are 18 quintillion others out there. Yet, despite the sheer vastness of it all, the universe is rather quiet. I move my controller’s right stick and look around the cockpit of my ship. My journey may be aimless, but I am engaged, not bored, and not quite challenged to the point of anxiety. My ship’s AI tells me that I am almost out of fuel for my pulse drive. I have a new goal which is within my skill set to meet, and my suit’s AI is here to provide helpful feedback. I make my journey at the pace I desire, and veer from it for as long as I like. There is a win state in this game, but then again, there are so many small victories to occupy myself with that I do not mind a certain aimlessness because it is never truly aimless. To this point, the game would be a serial completionist’s nightmare. For example, if you were to spend only one second on each planet and not factor in travel time (which can be significant), it would take about 585 billion Earth years to see every in-game planet. Considering that we expect our sun to burn out of hydrogen in about 5.5 billion years, the game’s universe is, for all intents and purposes, infinite. That said, how could one call an endless universe with a loose and vague objective a game?

In writing this, I consider the 100 hours I’ve spent in the game. I consider what I have accomplished—the discovery and exploration of numerous planets, as well as the categorization of many species of flora and fauna. I built a trade network that spans solar systems through a series of settlements, mining operations, and trade vessels that I’ve constructed, pirated, or negotiated for along my seemingly Sisyphean journey to the center of the universe. I wonder what my choices in this universe reveal about me and my preconceived notions regarding power and empire. However, the journey has also been a familiar one. It is built upon tried-and-true game mechanics à la Minecraft—mining to refine, refining to construct, only to mine and refine and construct more efficiently. At base, and more familiar still, the game seems to align with Koster’s (2013) assertion that “classifying, collating, and exercising power over the contents of a space is one of the fundamental lessons of all kinds of gameplay.” This concept rings true in No Man’s Sky, as the player literally discovers and classifies various species for in-game currency. However, despite its size and sci-fi trappings, the game is about something even more profoundly human—survival. Moreover, I argue that the ways in which we choose to survive in No Man’s Sky as we continue our journey to the center of the universe say much about ourselves and the very purpose of play.

Game Overview

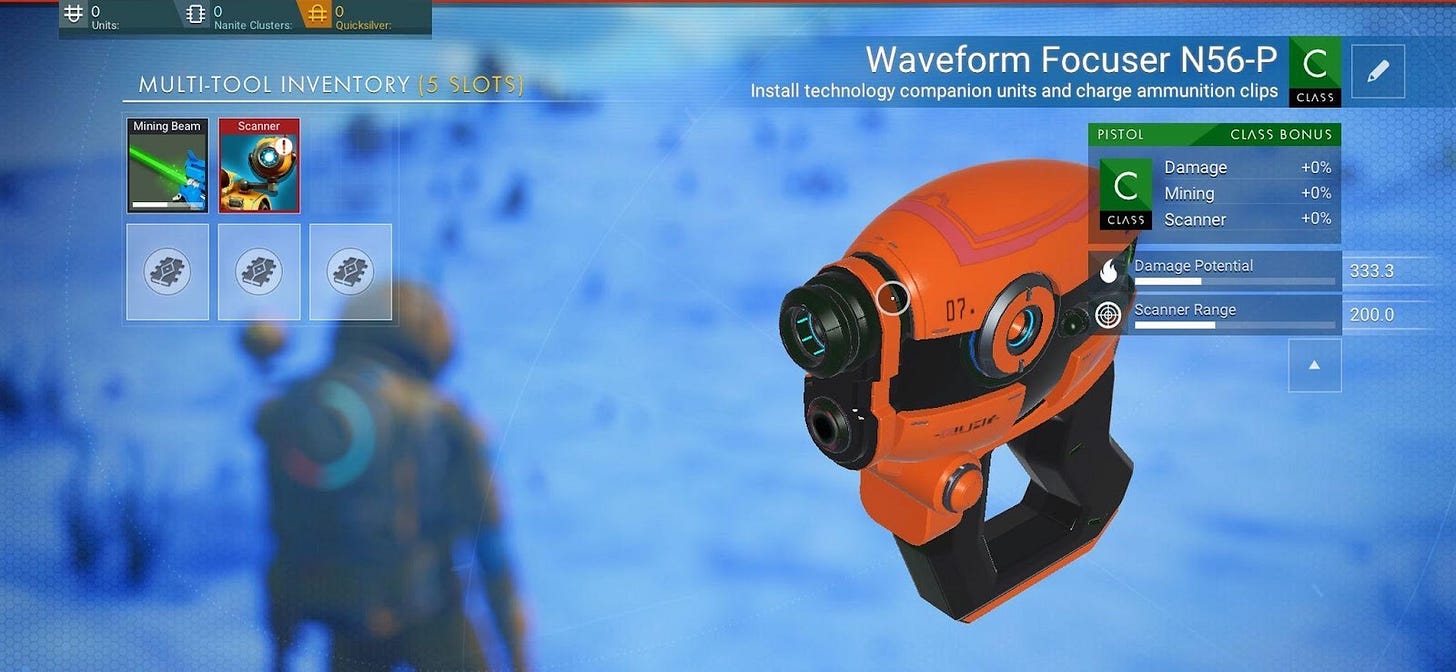

At base, No Man’s Sky is a game of discovery, expression, fellowship, and fantasy to borrow Hunicke, LeBlanc, and Zubek’s aesthetic taxonomy (2004, p. 2). The in-game aesthetics stem from how players interact with the game’s core mechanics—time, tools, minerals, and planets (specifically, each planet’s climate, geography, culture, and resource distribution). Scarcity is the immediate challenge players face. Every tool you own and every technology you engineer runs on some kind of fuel or requires a specific part to continue functioning. The challenge of resource management coupled with the breakdown of necessary tools makes for a satisfying gameplay loop that is again similar to Minecraft, but different in that the in-game threat comes not from a horde of night creatures, but rather from more passive sources like atmospheric toxicity, intense radiation, extreme temperatures, and the occasional aggressive inhabitants, pirates, or parasitic alien organisms (beware dilapidated frigates).

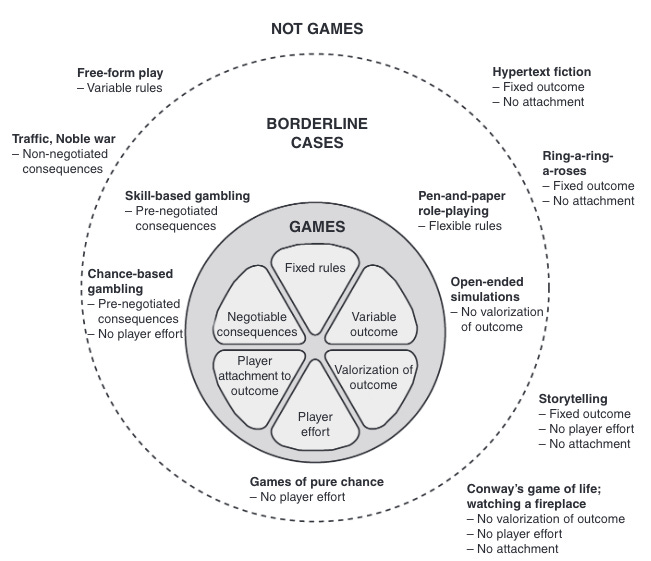

In order to look closely at No Man’s Sky, we must first determine where it finds itself among the many definitions of games. Juul’s (2003) configuration of what constitutes games, borderline cases, and “not games” serves as a useful starting place. No Man’s Sky features all of the core mechanics of a game as described in the figure below.

However, while No Man’s Sky has fixed rules (e.g., if your life support system fails, you die), and while the player may be attached to the game’s outcome as they invest countless hours to further their journey to the center of the universe, the win state is such that the game eschews valorizing outcomes and spurns the concept of negotiable consequences. The game takes cues from open-ended simulations and free-form play where the journey, more than the destination, is what truly matters.

No Man’s Sky, with all of its procedurally generated planets, has shown us through its years of frequent updates and DLCs that it consistently has something new to teach us. It is through this constant tinkering, updating, and expansion of the game that the developers skirt around Koster’s (2013) definition of a good game, “one that teaches everything it has to offer before the player stops playing,” by maintaining a game in such a way that it may never stop teaching us for as long as the developers add new, free, and interesting mechanics that alter the play experience. The numerous patches, DLCs, and updates are not quite a reinvention of the initial game as much as they are an expansion of, or a fulfillment of, the promise that the game made upon its initial release. The game is ‘good’ or ‘fun’ insofar as its size, scope, vision, and new, rewarding challenges have players revisiting it time and again to learn more about this boundless universe from its inception to its present-day iteration. Moreover, this trend does not seem to be slowing. One only has to look at reporting from both game and general tech publications for evidence of the claim. Countless articles and video essays taking a stab at “revisiting” or “re-evaluating” the game and its burgeoning legacy. That said, my thoughts regarding the game extend beyond Koster’s definition of a good game or the newfound admiration of reporters and critics. McGonigal (2011) points out that “[i]n a good...game you’re always playing on the very edge of your skill level, always on the brink of falling off. When you do fall off, you feel the urge to climb back on. That’s because there is virtually nothing as engaging as this state of working at the very limits of our ability” (p. 24). You might call this flow. To this point, No Man’s Sky also succeeds.

Gameplay Analysis

I wake up stranded on a planet with no recollection of how I got there. The atmosphere is highly toxic. I do not know where my ship is, and my life support systems are failing. In other words, the game tosses players into a dire situation. However, it is also here that I first learn from the game. It teaches me the fundamentals of mining and life support systems. I quickly learned that to survive, I would need to mine sodium to recharge my hazard protection systems. The space suit’s handy AI helps players figure out how they may go about finding sodium. I pressed the right stick, and my suit’s visor ran a scan of the surrounding environment, marking a nearby sodium deposit. Once I reached it, I used my mining beam to collect the mineral, which recharged my life support. In other words, the game’s mechanics (a toxic atmosphere) interacted with my failing life support system, which caused my health to decrease (dynamics), and worried me enough (aesthetics) to gather a surplus of sodium.

It is in the early game that I would like to focus my consideration on moments of in-game learning. In such an expansive universe with so many things that can go wrong, the game risks overloading a player with too many choices, too many problems, and too many opportunities, too early on. The developers solve this problem by introducing you to the most basic dangers and needs and then scaling up from there. Yes, while starting with a starship, stable climate, and a set of awesome technologies would be great to get the player exploring the universe quickly, it would likely be damaging in the long run as the player would not understand the fundamentals that the game is built upon, nor how all of the different in-game systems build upon one another. Being given everything from the start would not equip the player to adapt the mechanics and technologies to novel situations and problems. At best, the novice player would have a shallow understanding of the things, but not of their functions and constituent elements. By learning the foundations and recalling them frequently within the gameplay loop, we develop the ability to plan and reason with the mechanics. This is where the game shares some similarities with Daniel Willingham’s ideas about critical thinking. The player cannot explore the universe or answer its many problems in a novel, self-directed, and effective way without first possessing the necessary background knowledge along with some meaningful practice in applying it (2016). Chief among this necessary background is how to mine and repair gear, which is where the game begins.

Once the player mines the necessary minerals and recharges their life support systems, they are prompted to locate their ship by heading to an SOS beacon. Each new challenge in the early game allows the player to practice a specific skill that builds their knowledge base, leading to mastery. However, just as the player masters, say, how to mine sodium, the game presents a new challenge—repairing your launch thrusters and pulse engine. This introduces a new game mechanic: starship repair. Raw materials like sodium and ferrite dust may not be useful in such an endeavor, and now the player must find a way to refine those minerals and create metal plating for the ship’s haul, or fuel for the launch thrusters. The game taught me the basics of survival in its universe; now it teaches me the basics of crafting. I mine the necessary materials, build a small portable refinery, and create the necessary objects to get my ship operational.

It is only when the player has mastered mining, crafting, repair, and survival that the game allows them to explore. James Paul Gee (2013) is instructive here. The information presented by the game is both just-in-time and on-demand. What those last two phrases mean in the context of J.P. Gee and No Man’s Sky is that the game gives the player a small piece of information at first, and the player must apply that information just as they learned it (e.g., your life support system is failing, you need sodium, go mine sodium). Moreover, as the player meets new and unanticipated challenges (e.g., their multi-tool fails), they must seek out more information on how to solve the challenge (i.e., use the menu to discover that you need carbon nanotubes, which require carbon that you can then craft into the necessary tubes).

As I described earlier in the paper, the game initially disregards much of its complexity and subsequently builds up to it. Gee (2013) would describe this as the “fish tank principle,” a simplified micro-world that keeps the core variables and relationships visible while temporarily removing distracting complexity. As learners grasp how the essentials interact, you gradually reintroduce additional elements, rules, and noise until they can handle the full ecosystem. However, as the game progresses and the player gets their ship off the ground, they escape the metaphorical fish tank and enter the wider sandbox, where they can explore, test, and try new things. As the game expands, so do the various issues and goals, which lead to more practice of key skills needed later in the game as you come across more complex situations that require you to use your skills in new, self-directed ways, like space combat, managing a settlement, or running trade routes.

Conclusions & Classroom Connections

No Man’s Sky, as I hope to have conveyed, has taught me a great deal about its underlying systems and best practices for succeeding on my journey. However, I am left to wonder whether the game’s mechanics resulted in anything other than in-game proficiency. Were there more implicit lessons with broader implications that apply to, say, a social studies classroom? An overarching concept from the game is that of systems thinking. I encountered a complex game world and was confronted with how my actions and other variables led to unforeseen consequences. I considered how ethical it was to strip planets of their resources to fuel an individual quest, with no regard for other species, outside of classifying them to make money from the discovery. The game taught me valuable lessons regarding scaffolding and the application of the cycle of expertise. Still, the game itself is likely not something I could use in a classroom without significant tinkering, design, and ultimately limiting what the students’ play experience would be. That said, the game allowed me to carefully consider the relationship between resources, trade, power, and ecosystem diversity. In sum, an endless universe with a vague objective, such as the one found in No Man’s Sky, is indeed a game. The developers scaffold the player’s experience in such a way that we are not dropped into a boundless world with no idea how to get what we need and meet our goals, but always with just enough information and just enough practice so that we are playing to the very edge of what we know. And that is a good game.

References

Baron, S. M. (2012, March 22). Cognitive Flow: The psychology of great game design. Retrieved from: https://gamasutra.com/view/feature/166972/cognitive_flow_the_psychology_of_.php

Egenfeldt-Nielsen, S., Smith, J. H., & Tosca, S. P. (2013). Understanding Video Games: The Essential Introduction (pp. 31-59). New York, NY: Routledge.

Gee, J. P. (2013, November 13). Jim Gee principles on gaming [Video]. YouTube.

Gee, J. P. (2013). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. New St. Martin’s Press.

Hunicke, R., LeBlanc, M., & Zubej, R. (2004, July). MDA: A formal approach to game design and game research. In Proceedings of the AAAI Workshop on Challenges in Game AI, 4(1), 1-5.

Klein, D. (2021, August 22). No Man’s Sky 5 Years Later. Gamespot. Retrieved from https://www.gamespot.com/videos/no-mans-sky-5-years-later/2300-6455970/.

Koster, R. (2013). A theory of fun for game design. O’Reilly Media, Inc.

McGonigal, J. (2011). Reality is broken: Why games make us better and how they can change the world. Penguin Press (p. 11).

Stuart, K. (2021, August 10). No Man’s Sky: give years of meteors, mining, and metaphysics.

The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/games/2021/aug/10/.

Tassi, P. (2021, July 30). ‘Cyberpunk 2077’ Is Way Off Schedule For A ‘No Man’s Sky’ Style

Comeback. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/paultassi/2021/07/30/

Willingham, Daniel T. “Knowledge and Practice: The Real Keys to Critical Thinking.” Knowledge Matters, no. 1, Mar. 2016, pp. 1-7.